From the Mouths of Murderers

This is the first chapter from Howard Bloom’s new book How I Accidentally Started the Sixties, about which Timothy Leary said,

“This is a monumental, epic, glorious literary achievement. Every page, every paragraph, every sentence sparkles with captivating metaphors, delightful verbal concoctions, alchemical insights, philosophic whimsy, absurd illogicals, scientific comedy routines, relentless, non-stop waves of hilarity. The comparisons to James Joyce are inevitable and undeniable. Finnegans Wake wanders through the rock ‘n roll sixties. Wow! Whew! Wild! Wonderful!”

(This stuff really happened. Several names have been changed to protect me from my attorney. However any lack of resemblance to actual people, living or dead, is solely due to the incompetence of the author.)

It feels a little funny to drag these stories from the depths of memory now that us baby boomers are all supposed to be picking out the patterns for our tombstones, counting our wrinkles, and trying to replicate the secret of Ronald Reagan’s perpetually dark hair.

But speaking as a voice from the crypt, let me see if I can impart some mangled semblance of wisdom to a seriously brain-damaged world. To follow this tale of moral profundity, you’ll have to travel with me back to the dim and distant days of a long forgotten time, before microwaveable popcorn, MTV, the affordable hand-held calculator and L’eggs panty hose. Yes, we are fumbling through the swirling mists of the past to those years of astonishing antiquity when even Johnny Carson was only middle-aged… THE EARLY SIXTIES!!!

More specifically, it was 1962. I had just left college without finishing my freshman year, a high crime in that primordial eon. Escape from an institution of higher learning before your sentence expired was so unheard of for a middle-class Jewish kid that there wasn’t even a name for the crime—just a mushroom cloud of incoherent curses that erupted when your parents discovered your abominable act. The phrase “drop-out” wouldn’t plop into the American vocabulary for years to come.

I’d camped out in the basement of a Seattle anthropologist with a remarkably hospitable nature—so hospitable, in fact, that the basement’s opposite end was occupied by a charming drag queen who could have given Josephine Baker lessons in haute couture. Somehow, this master of the plumed gown and feathered boa had no influence on our host. But apparently, I did. In fact, I accidentally became our housing provider’s spiritual master.

So the anthropological type decided to abandon his mortgage, forget about his teaching job, leave his unfinished Ph.D. thesis about decorative penis cones in the South Pacific, grab his girlfriend, and follow me and two of my friends to California.

Our arrangements for departure were all set. We would head for the nearest freight yard and catch a box-car headed south. Unfortunately, I got a cold, and my followers left me to catch up with them when I could get better. Not a nice thing to do to your spiritual leader.

But they weren’t heartless about it. They found me a room in one of those environmentally-conscious University of Seattle off-campus hovels where no student has washed the dishes for six months and every platter and fork is turning mossy in the ecosystem of the sink. I had a mattress of my own on a nice, hardwood floor. The boards were biodegradable. You could tell—they were rotting. And my acolytes had provisioned me for my convalescence with a leaking pitcher of orange juice, a pile of sandwiches, and the company of a remarkably sympathetic horde of cockroaches.

Four days later, thanks to the healing powers of this nature-rich habitat, I finally got my health back. I went to the local supermarket, gently laid a quart of milk and a loaf of bread in my shopping cart, then stuffed my athletic supporter with provisions—cream cheese, smoked oysters, and a variety of other delicacies. I paid for the milk and the bread, accepted the more expensive items as a donation, and headed back for the moss-covered kitchen, where I cleared a space between the fungi, spread out my 24 slices of bread, made 12 sandwiches, packed them in the plastic bag provided as a bonus by Wonder Bread, made a gallon of Kool-Aid in a Clorox jug salvaged from the trash barrel of a nearby laundromat, rolled the victuals into my sleeping bag, headed for the open road and stuck out my thumb. Jack Kerouac, one of my idols at the time, would have been proud.

My apostles had ridden the rails. I had decided to travel by road. Unfortunately, hitchhiking is an unreliable form of transportation. There are no regularly scheduled pickups. You depend on the milk of human kindness. And the cows that produce this stuff are apparently an endangered species. So, as usual when I propped myself in the gravel by a stretch of tarmac, I was stuck. In eight hours, I’d zoomed a full 75 miles. Now I still had a thousand left to go before reaching my destination—the fabled cities by the San Francisco Bay.

For four hours I had been sampling gourmet exhaust fumes on a two-lane blacktop that ran through a collection of five buildings called Eugene, Oregon. Every 20 minutes or so, an approaching car lifted my hopes to the stratosphere, then dropped them without a parachute as it disappeared over the horizon. I attempted to summon each vehicle’s return with wistful looks. But much as Walt Disney had assured me that “when you wish upon a star your dreams come true,” Walt—and innumerable drivers—seemed to be letting me down. Maybe my problem was that it was still daylight.

As dusk turned the countryside grey and the first pinpricks of celestial luminescence appeared in the black and blue sky, my fate went through a sudden alteration. An old, hearse-black Hudson rattled in my direction, flapping the random pieces of tin from which it was made in an effort to warn any cows grazing on the asphalt of its approach.

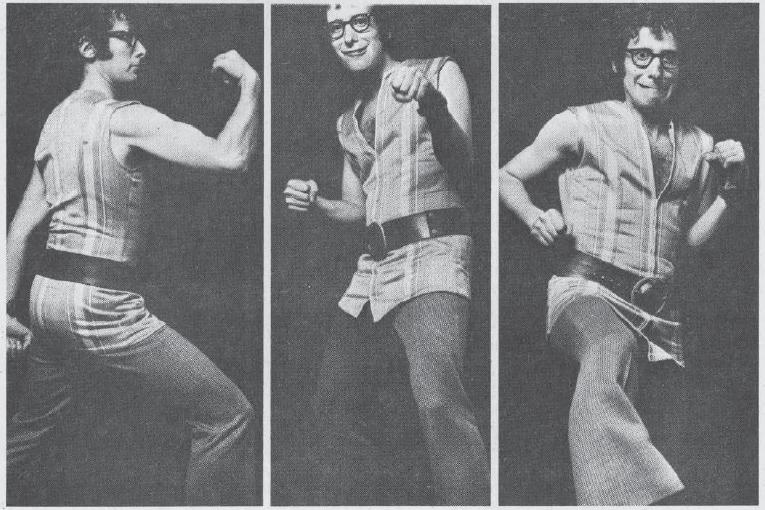

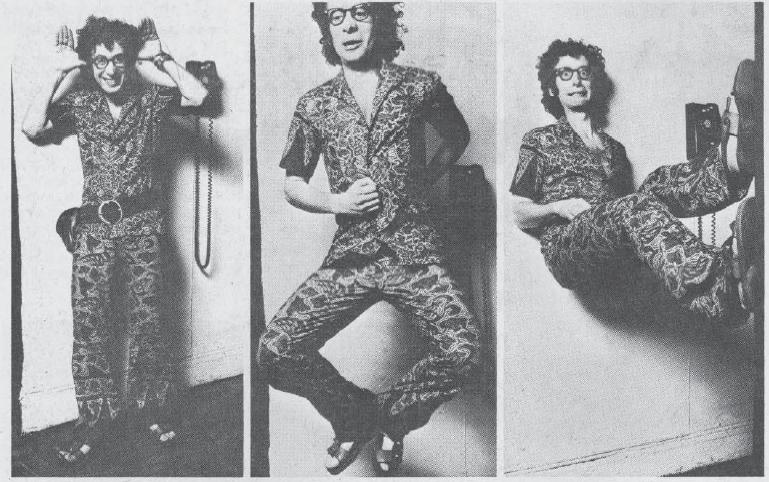

My spirits, as usual, went up like a weather balloon. The auto grew near and actually slowed down. Then the inhabitants apparently looked me over carefully, noted that I was barefoot and had a Harpo Marx haircut of a kind unknown to Western Civilization for roughly 300 years (the Beatles hadn’t arrived to make long hair acceptable yet, and even when they would, their mop-tops would not emerge from their scalps like foot-long worms curled in terminal pain). The auto’s inhabitants saw that I was carrying a thoroughly disreputable sleeping bag packed with food and my one extra piece of clothing, an ultra-baggy, bargain-basement white sweater. They were unable to spot my major virtue—I showered every morning. The inspection was apparently unsatisfactory. They picked up momentum and left me in their dust.

The sun had sunk, the clouds on the horizon were red, and so were the whites of my eyes. Eugene, Oregon, was disappearing into the gloom along with my hopes, the sort of experience that makes a rejected hitchhiker feel as if his emotions have been plunged into liquid nitrogen. Then a miracle occurred. The funereal Hudson appeared on a side road about 250 feet behind me. Disney’s star had worked! The car’s inhabitants had debated about me, changed their minds, taken a left, looped around a patch of farmland, and returned.

The dusty rear door of the ebony car opened, spilling two dozen empty beer cans into the street. A pale, white hand emerged from the dark interior and gestured. I snatched my sleeping bag and ran, hoping to catch up with this chariot before it could swing across the Jordan without me. It was the beginning of one of the strangest nights of my life.

To enter the car, I had to find space for myself on a back seat whose legroom was occupied by four cases of beer. Inside, the figures rescuing me were spectrally silent. A gaunt, tall man clutched the steering wheel, staring straight ahead. In the dusk, his eye sockets looked like huge black holes. The passenger seat held a smaller person with slick, dark hair who never turned his head. And ensconced on my left was the most genial of my hosts, a round-faced fellow who silently bid me make myself comfortable before he, too, riveted his eyes on the front window and imitated an extra from Night of the Living Dead.

I asked where my charioteers were going, knowing that if I was in luck I’d be carried 50 or 60 miles before I was let out to unfurl my white sweater (designed to allow motorists to see me at night) and try for my next brief hop down the long road to Berkeley, California. A voice welled up somewhere in the car—I couldn’t quite tell from whom—with the most welcome—though ghostly—syllables I’d heard in days: “San Francisco.” These saviors were destined to take me my full 1,000 miles!

One of the joys of hitchhiking is conversation. It’s a delight to yank life stories from the unsuspecting benefactors who haul you around. My luck in this sport had always been superb. I’d pulled inner secrets out of a carnival barker, a narcotics agent, a Bible College graduate who was fleeing from a conspiracy between flying saucer people and the CIA, and even from an insurance salesman who explained with extraordinary warmth why his kids and wife were more important to him than his career.

“What do you guys do for a living,” I asked. This was the question that generally gives you the key with which to roll open the top of the biographical sardine can.

But not tonight. My three hosts stared straight ahead. The eye sockets of the driver grew more cadaverous. The last light disappeared from the sky beyond the windshield. No one said a word. I tried a few more questions. Silence… except for those rare occasions on which a hollowed-out voice would ask the slightly pudgy figure in the gloaming next to me for another can of beer.

I resigned myself to looking out the side window at the blackness of the countryside. Then, after half an hour, one of my dark angels of transportation asked a brief question. “You don’t mind a little heater action, do you?” It was getting chilly. So I answered that I didn’t mind at all. But no one reached for the dashboard switch that would have pumped some warmth. Then slowly it dawned on me—a faint recollection of Sergeant Joe Friday on the 1950s TV show Dragnet. A “heater” was a gun.

I sat in a cold sweat with mental pictures of my limp body tied to a telephone pole in the desert, slightly marred by a bullet hole in the head. After all, who else was there to shoot? The answer emerged ten minutes later when we pulled into a lonely country gas-station—one of those all-purpose numbers that’ll sell you everything from a spark plug and a sausage to an extension cord. The pudgy gentleman next to me and the fellow from the passenger seat disembarked and headed for the modest hut’s screen door. The tall skeleton at the wheel kept the engine running, and his nerves glued to the open road.

Through the plate glass window I could see an elderly man behind a counter. I waited for a bang, spurting blood, and the spectacle of the gray-haired store-owner falling over backwards with a startled look on his face, knocking a couple of cans of pork and beans off the shelf. Then I expected to see the duo in whose car I was scrunched running from the shack with greenbacks spilling from their fists.

Nothing of the sort occurred. When the gunmen headed back to the car, the senior citizen was still upright. His would-be terminators were less so. In fact, their postures had been infected by a definite slump. The two slipped back into their places in the Hudson and angrily slammed the doors. Then we took off.

Turned out my companions had been attempting a quick-change routine. Such was their expertise that they’d gone in prepared to offer a twenty and get change for a hundred. They’d ended up with change for a ten. Oregonian country store operators are apparently a shifty lot.

The failure was humiliating. So humiliating, in fact, that the trio felt compelled to rescue its dignity. Thus they finally confessed their line of business. The driver and his partner in the front seat were specialists in armed robbery. They were particularly proud of their ability to break into fur vaults in the wee small hours and make off with skins that numerous undersized animals had donated to provide warmth for status-starved females of the human upper crust. At the moment, the pair were out on bail pending trial for one of their more spectacular heists.

The guy in the back seat was the one who had botched the short change deal and made the whole gang look like suckers in front of a total stranger. Despite his moronic fuck-up, they allowed him to announce his claim to fame. He was a con-man. Judging from his recent performance, it was a miracle he made a living.

It would take more bragging than this to recover the pride the group had lost, and they knew it. So the driver removed the coffin-lid from his larynx and confessed the details of his hobby—murdering his fellow men. Well, in reality, his victims weren’t reallymen. They were Indians, a species he was sure fell on the evolutionary ladder somewhere below toilet algae. But that didn’t keep the sport from having its moments of excitement. Like there was the septuagenarian red man our driver had beaten up and shoved over a cliff at a garbage dump. And there were a variety of others on whom he’d demonstrated his marksmanship. So, he’d missed a few of his shots. But, he assured me, there were enough Native American brains splattered around the Northwest Pacific to indicate that when he really concentrated he could actually hit a target.

Turns out they’d picked me up because they were heroin addicts and the supply of drugs in their home town, Vancouver, had dried up. They were hoping to score some dope in San Francisco and the sight of my outfit—long hair, no shoes, etc.—had convinced them I’d be able to provide leads on where to find injectable materials. Unfortunately, the only drug dealers I was aware of sold aspirin.

Before their poppy-starved metabolisms could freeze a turkey, they were attempting to stave off agony with substitute chemicals. Hence their oversized supply of beer.

Eventually the tale of noble deeds—robbery, homicide and such— petered out. They put a final frosting on their image of machismo by trading lengthy epics of all the women who had given them oral sex, comparing fine points of lingual techniques too technical for me to follow as they allegedly attempted to ascertain which woman had the most acrobatic mouth in Western Canada. But eventually, they ran out of peculiarly-shaped throats and other feminine orifices to compare, and were left with nothing to say. After all, it takes a long time to drive a thousand miles.

The lack of entertainment and the deprived status of their endogenous morphine receptors was beginning to drive them crazy. Finally, in a last-ditch effort to entertain themselves, the homicidal threesome started to ask questions about what I did to sustain myself. I told them how I had dropped out of school to seek Satori—the ultimate state of Zen enlightenment. This did not exactly thrill them. I offered them some of my cream-cheese and smoked oyster sandwiches. When they heard that the oysters had been transported from the Safeway in an athletic supporter, they mysteriously lost their appetites. What’s worse, this revelation of my life of crime (to wit, nourishing myself and my friends at the expense of large supermarkets), threw them into a frenzy of moral disturbance. They feared for the fate of my soul. When we got to the fact that I hadn’t seen my mother in over nine months, they became hysterical.

It was obvious that they had an emergency on their hands—a human about to self-destruct. Like a team of paramedics, they mobilized to affect my rescue.

First they outlined the error of my ways. I was living without real goals, they said. No human being could do that. You needed a nice, steady relationship to give your life some meaning—like the ones they had with the girlfriends they cheated on back home. If they didn’t save me fast, they could see I was going to tumble straight into hell, and they were desperate to catch me before I fell. What’s more, I HAD to go home to see my mother!

So the visions of being tied to a telephone pole disappeared from my head, and between midnight and dawn I received caring, fatherly lectures on how to lead a moral life from folks who poked lead into other people’s brains for amusement. Damon Runyon was right. There’s honor, and even generosity, among thieves.

An hour after sunrise, the moral lectures stopped. Something almost too exciting to contemplate was coming up. We were about to cross the Golden Gate Bridge. This was the first chance in their lives for my traveling companions to see the Disneyland that every con man and murderer dreams about, the ultimate tourist attraction for felons: Alcatraz. As they caught a glimpse of the fabled island in the mist across the water, all three of them squealed like five year olds.

The strange thing is this. Over the next 20 years, I’d get a lot of advice from truckdrivers, migrant fruit pickers, psychiatrists, psychologists, corporate presidents, and even rock and roll stars. But in the end, I’d make a simple discovery. When it came to the meaning of life, the murderers had been right. You need a woman.

How I Accidentally Started the Sixties is the tale of how I found that out. Buy it at Amazon.com